Tycho Brahe

Michael Fowler, UVa Physics

Tycho Brahe, born in 1546, was the eldest son of a noble Danish family, and as such appeared destined for the natural aristocratic occupations of hunting and warfare. However, he had an uncle Joergen, a country squire and vice-admiral, who was more educated, and childless. Tycho's father had agreed with the uncle before Tycho was born that if Tycho was a boy, the uncle could adopt and raise him. He changed his mind and reneged. Then, when a younger brother was born, the uncle kidnapped Tycho. The father threatened to murder the uncle, but eventually calmed down, since Tycho stood to inherit a large estate from the uncle.

When Tycho was seven, his uncle insisted that he begin studying Latin. His parents objected, but the uncle said this would help Tycho become a lawyer. At age thirteen, Tycho entered the University of Copenhagen to study law and philosophy. At this impressionable age, an event took place that changed his life. There was a partial eclipse of the sun. This had been predicted, and took place on schedule. It struck Tycho as "something divine that men should know the motions of the stars so accurately that they were able a long time beforehand to predict their places and relative positions". Perhaps this predictability was especially appealing to one whose personal life was evolving in rather an uncertain way. One of the advantages of being a rich kid was that he could immediately go out and buy a copy of Ptolemy's Almagest (in Latin) , and some sets of astronomical tables, which showed the positions of the planets at any given time. Ptolemy himself had made such tables, and they had been revised in Spain by a group of fifty astronomers in 1252, brought together by Alfonso X of Castile. These were called the Alfonsine tables. Tycho also bought a recent set of tables based on Copernicus' theory.

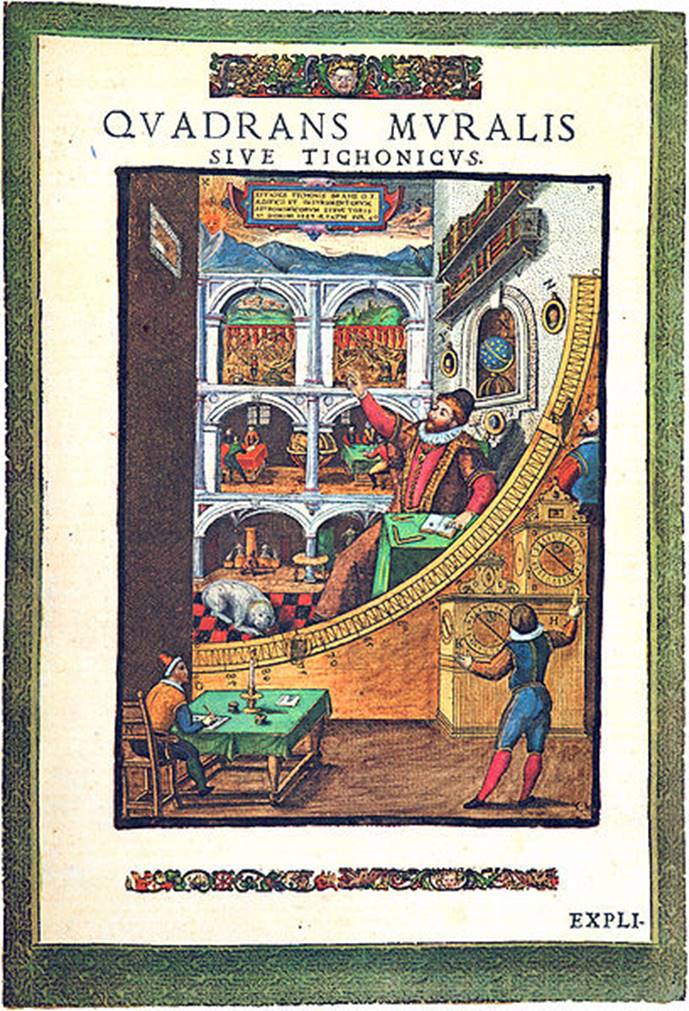

At age sixteen, the uncle sent Tycho to Leipzig, in Germany, to continue his study of law. He was accompanied by a tutor, the twenty year old Anders Vedel, who himself later became famous as Denmark's first great historian. However, Tycho was obsessed with astronomy. He bought books and instruments, which he hid from his tutor, and stayed up much of each night observing the stars. When he was seventeen, he observed a special event--Jupiter and Saturn passed very close to each other. (This was on August 17, 1563.) He found on checking the tables that the Alfonsine tables were off by a month in predicting this event, and the Copernicus tables off by several days. Tycho decided this was a pathetic performance by the astronomers, and much better tables could be constructed just by more accurate observation of the exact positions of the planets over an extended period of time. He decided that this was what he was going to do. Vedel realized Tycho was a hopeless case, and gave up trying to tutor him in law. The two remained good friends for life. Meanwhile, the uncle died of pneumonia after rescuing the king from drowning after the king had fallen off the bridge to his castle returning from a naval battle with the Swedes. When Tycho returned to Denmark, the rest of his family were quite unfriendly. They despised his stargazing, and blamed him for neglecting the law. He decided to return to Germany, and fell in with some rich amateur astronomers in Augsburg. He persuaded them that what was needed was accurate observation, and (as telescopes had not yet been invented) this meant rather large quadrants to get lines of sight on stars. They set up a large wooden quadrant, part of a circle with a nineteen foot radius, that took twenty men to set up. It was graduated in sixtieths of a degree. This was the beginning of Tycho's accurate observations. (Image from Wikimedia Commons.)

One unfortunate incident during his stay in Germany suggests that Tycho inherited his father's rather hot-headed ways. Tycho lost his temper in a quarrel with another student over who was the better mathematician, this led to a duel in which part of Tycho's nose was cut off. The lost piece was replaced by a gold and silver alloy, and Tycho always carried around with him a snuffbox containing some "ointment or glutinous composition" which he frequently rubbed on his nose, possibly to keep it stuck on (The Sleepwalkers, p 287 - see references at end)).

At the age of twenty-six, in 1570, Tycho returned to Denmark. He lived for a while with his family, then with an uncle, Steen Bille, who had founded the first paper mill and glassworks in Denmark. He was the only family member who approved of star gazing.

In 1572, another astronomical event took place that changed Tycho's life. On November 11, walking back from Steen's alchemy lab, Tycho noticed a new star in the sky that was brighter than Venus. He did not believe his eyes. He called some servants, then some peasants, to reassure him that it was really there. The new star was so bright that it could be seen in daylight. It lasted eighteen months. It was what is now called a nova, a rare event. The crucial question from the astronomical and theological point of view was, where exactly was this new star? Was it an event in the upper atmosphere, that is to say, below the moon, what was then termed in the sublunary region? If so, that would be o.k., because this region, below the moon, was where change and decay took place. On the other hand, if it was out there in the eighth sphere, the fixed stars, the edge of heaven, that contradicted Aristotelian and Christian dogma, because that sphere had remained unchanged since the day of creation, and was supposed to stay that way. Maestlin in Tubingen, and Thomas Diggs in England, leading astronomers, tried to detect movement in the new star by lining it up with known fixed stars, using stretched threads. They could see no movement. Tycho had just finished building a new sextant, with arms five and a half feet long, a massive bronze hinge, a metallic scale calibrated in minutes (sixtieths of a degree) and a table of corrections for the remaining tiny errors in the instrument he had detected. His technology was far ahead of the competition, and he was able to settle the argument. The new star did not move at all relative to the fixed stars. It was in the eighth sphere. Tycho published a detailed account of his methods and findings the next year. He hesitated some time before publishing, because book writing seemed a bit undignified for a nobleman. Similarly, when some of the other young nobles asked him to give a course on astronomy, he refused, and only changed his mind when the King told him to do it.

By 1575, Tycho was famous throughout Europe, and he embarked on a grand tour, visiting astronomers in many cities. He decided it would be nice to move down to Basle, in Switzerland, a charming and civilized town. King Frederick II of Denmark (whose life had been saved by the uncle) was very upset at the thought of losing his best astronomer (and astrologer), and, after offering Tycho various castles, which didn't prove persuasive, offered him a whole island, flat with white cliffs, about three miles long, called Hveen, near Hamlet's castle of Elsinore. Denmark would bankroll building of an observatory and house, and the inhabitants of the island, who worked forty farms grouped around a small village, would become Tycho's subjects. The reason a king of a rather small country had quite so much wealth at his disposal was that the Protestant Reformation had placed the Church's lands and resources in his hands.

Tycho hired a German architect and built his Uraniborg (castle of the heavens). It was surrounded by a square wall 250 feet on a side. It had an onion dome, like the Kremlin, but an Italianate palace facade. It had rooms for huge precision instruments, fantastic murals, a paper mill and printing press, an alchemist's furnace, and a prison for tenants who caused problems. In the library, Tycho installed a brass globe five feet in diameter he had made for him in Augsburg. This was a highly polished accurate sphere, and the positions of the stars were engraved on it as they were measured over a twenty-five year period. In Tycho's study, a quadrant was built into the wall itself, with a mural of Tycho painted on to the wall.

The quadrant was centered on an open window through which the observations were made. Several clocks were used simultaneously to try to time the observations as precisely as possible--an observer and a timekeeper worked together. His very large staff and several sets of equipment permitted four independent measurements of the same thing simultaneously, greatly reducing the possibility of error. The precision of measurements, which had held at ten minutes of arc since Ptolemy, was reduced at Uraniborg to one minute of arc. The observatory was full of gadgets--statues turned by hidden mechanisms, and he had a system of bells he could ring in any room to summon assistants. There was a constant stream of distinguished visitors: princes, savants, courtiers, even King James VI of Scotland. The hard-drinking Tycho threw tremendous feasts for his visitors, at which occasionally silence was ordered to listen to the musings of a dwarf called Jepp, whom Tycho believed had second sight. He also had a tame elk, which died one night stumbling downstairs after too much strong beer (I am not making this up). He had many children, but under Danish custom they were all considered illegitimate, because his wife was a peasant woman.

Meanwhile Tycho abused his tenants in an appalling fashion. He made them work and provide goods to which he was not entitled, and threw them in chains if they gave trouble. Unfortunately for Tycho, King Ferdinand died in 1588, of too much drink, as mentioned by Vedel in the funeral oration. The new young king, Christian IV, wrote several letters to Tycho which were unanswered, and Tycho flouted even the high court of justice by holding a tenant and all his family in chains. Finally, measures were taken to reduce Tycho's income to more reasonable proportions, and as the years went by, Tycho was getting bored on the island, so in 1597, he got together his family, assistants servants, Jepp the dwarf and most of his equipment, and started to move across Europe in search of a suitable new place to set up an observatory. All his instruments could be dismantled and transported, because, he said, "An astronomer must be cosmopolitan, because ignorant statesmen cannot be expected to value their services" (The Sleepwalkers, p 299).

Once outside Denmark Tycho decided to give the young king a second chance, and wrote him that he would be willing to come back, but the king must understand that the terms had to be more agreeable to Tycho. The king's response can be summarized as "Forget it". Over the next two years, he stayed in several German towns, then in 1599, the entourage arrived in Prague, Bohemia, where the Emperor Rudolph II appointed Tycho imperial mathematicus, at a salary of 3,000 florins a year, and gave him the castle of his choice.

References:

Much of this lecture follows fairly closely Arthur Koestler's book The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe, Arkana Books.

The Sleepwalkers quotes explicitly referenced above are actually originally from the standard biography, Tycho Brahe, by J. L. E. Dreyer, Edinburgh, 1890.

I also used a physics book, Physics for the Inquiring Mind, by Eric Rogers, Princeton.