Binary Stars and Tidal Forces

Michael Fowler

Binary Stars

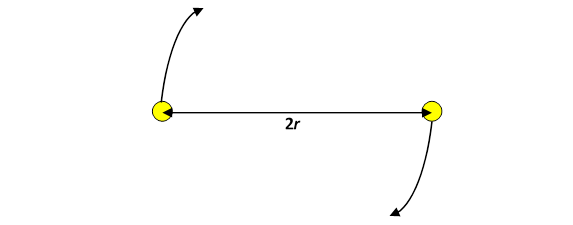

Up to this point, we’ve been considering gravitational attraction between pairs of objects where one of them was much heavier than the other, and was taken to be fixed. That is an excellent approximation for the Sun and the planets, or the planets and their satellites, but is not perfect. To see where it really breaks down, consider a binary star system with two equally massive stars. (Binary star systems are quite common, in fact most stars are in them.) In the simplest case, the two stars will orbit each other in circles, or, rather, by symmetry they will orbit a common central point:

For this equal-mass case, the equation becomes:

Problems with more than one rotating body turn out to handle more easily if the acceleration is written rather than That’s because is the same for the two stars, isn’t, except in the special case of equal mass.

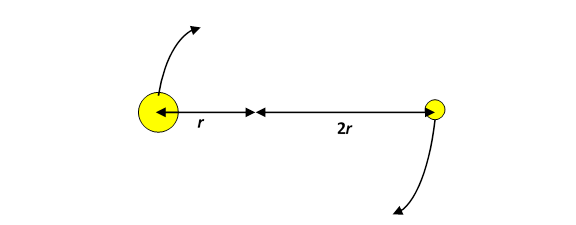

Consider now a binary system in which one star has mass M, the other 2M, but stay with the simple case of circular orbits. This time both stars go in circles around the common center of mass, and of course both move at the same angular velocity ω, so their accelerations are respectively, the accelerations are in inverse proportion to the masses, as they must be since both experience the same magnitude force, their mutual gravitational attraction.

The Earth-Moon System: Tidal Forces

The Earth’s mass is about eighty times the Moon’s mass. This means that the Earth and the Moon both circle the system center of mass, a point about one-eightieth of the way from the center of the Earth to the center of the Moonabout 3,000 miles from Earth’s center, so still inside the Earth.

To compute the Moon’s orbital period, if we need to be precise, we should adjust the equation previously used to

where is the Earth-Moon distance, and is the Moon’s distance from the system center of mass. Putting gives close to 1% accuracy, usually adequate for our purposes here, but clearly not for precision astronomy.

Another important point is that to find the gravitational force on the Moon, we take it to be the same as if all the Moon’s mass were concentrated at a point in the center. Assuming the Moon is spherically symmetrical, this is OK. We’ve established that the force on a mass outside the Moon is the same as if all the Moon’s mass were at the center, so, since the gravitational forces are equal and opposite, the force on the Moon from the mass is the same as if all the Moon’s mass were at the center. Therefore, the gravitational force of the Earth on the Moon, which can be thought of as the sum of all the one kilogram masses making up the Earth, must be the same as if all the Moon’s mass were at the center.

Weighing Rocks on the Moon

To understand how the Earth’s gravitational pull, and the Moon’s orbital motion around the Earth, affect the apparent value of gravity on the surface of the Moon, we imagine having a set of identical rocks which we weigh with identical spring scales at different points of the Moon, as shown in the diagram below. Now, a spring scale is just a spring which compresses when a weight is placed on it, the amount of compression of the spring is linearly proportional to the weight added (within the design range of the scale) and as the spring compresses it turns a pointer hand around a dial. The dial then records the weight. Well, actually, to be precise, the dial records the force the spring is exerting on the rock: the normal force that is, the same force the rock would experience from the ground if it were just resting on the ground.

So, the forces on the rocks A, B, C shown are:

1. Their Moon-weights all directed towards the center of the Moon, and all equal in magnitude,

2. The normal forces from the compressed springs they’re resting on (not shown),

3. The Earth’s gravitational pull, the blue arrows in the diagram, decreasing with increasing distance from Earth.

Since the rocks are going round the Earth with the Moon in its orbit, their accelerations towards the Earth are , where is the distance of that particular rock from the center of the Moon's orbit (which is inside the Earth). This acceleration increases with distance from the Earth, since is the same for all of them. Fig 3

Remember that the Earth’s total gravitational pull on the Moon is the same as if all the Moon’s mass were concentrated at the Moon’s central point. If we assume rock A in the diagram to be the same distance from Earth as the center of the Moon (it's close), it will feel the same gravitational pull towards Earth as a point mass at the center of the Moon, and therefore will accelerate towards Earth at the same rate: it will stay with the Moon, with no tendency to move towards or away from the Earth. Meanwhile, in the perpendicular direction, the spring balance it’s resting on measures the force N with which the spring is supporting it, and this equals its weight W, meaning how strongly attracted it is by the Moon’s gravity.

Now consider rock B on the left, closer to earth. It will feel a stronger gravitational pull from the Earth, than rock A does, yet its acceleration is less than rock A’s accelerationr is less, and is the same.

What about ?

There must clearly be some force opposing the Earth’s gravity, since B’s acceleration towards Earth is less than that given by the Earth’s gravity acting alone. And there is: the Moon’s gravity, the rock’s weight pulls it the other way. But isn’t the weight balanced by the spring force ? The answer is, it cannot be, since we always have . We are forced to conclude that the magnitude of the spring force the Moon-weight registered on the dial of the scale, is less than its true Moon-weight (as would be measured at A.)

The basic result is that on the part of the Moon closest to the Earth, things register lighter on the spring scale: and, therefore, it’s easier to lift something, Moon-gravity is effectively lessened by the Earth’s pulling things “up”.

Let’s now look at rock C. Being further from the Earth, but going around with the Moon at the same angular velocity its acceleration is greater than rock A’s, but the Earth’s gravitational pull is weaker at the greater distance.

Again, to satisfy the Moon’s gravitational pull on the rock at C, must be out of balance with the force from the spring. In fact, the net force from these two must point left (towards the Earth) to give the greater acceleration. Therefore, the Moon’s gravitational pull must be stronger than the normal force from the surface (meaning the spring). That means that a rock at C placed on a spring scale will register a smaller weightthe same effect as at B! Things register lighter at the furthest point from Earth as well!

This means that rocks at B and C will experience what amounts to an apparently lower gravitational pull to the Moon’s center than a rock at A. Imagine now that the Moon were covered with an ocean. The effectively stronger gravity at places like A would pull the water down more than the weaker effective gravity at B, C. This is the origin of tides: the high tide is where “gravity” is weakest, on two opposite sides. Of course, there is no ocean on the Moon, but this same argument works for the effect of the Moon’s gravity on the Earth: remember the Earth is also circling the Earth-Moon system center of mass.

Devastating Tidal Forces

If the Moon spiraled closer to the Earth at some distant future date, the tidal forces would severely distort its shape, to a prolate ellipsoid (cigar shape) pointing towards Earth. At some point, it would break up. This critical distance is called the Roche limit, and depends on the strength of the forces holding the Moon together, and of course on the size of the Moon. It explains a lot: why are there no big planets close to the Sun, how far can a moon be from its planet, what is the nature of Saturn's rings. Maxwell proved in a student essay that Saturn's rings, if solid, would be torn apart by tidal forces, so they must be made up of circling rocks. A famous case was the tidal tearing up of comet Shoemaker Levy 9, which ended its life orbiting Jupiter. It passed within its Roche limit, broke up, then a little later crashed into Jupiter.

The strongest tidal forces occur in black holes: if you fall into one, you will be torn apart by the relative gravitational forces on your head and your feet. Further in, atoms are torn apart, and ultimately protons.