Analyzing Waves on a String

Michael Fowler, University of Virginia

From Newton’s Laws to the Wave Equation: a Tiny Bit of String

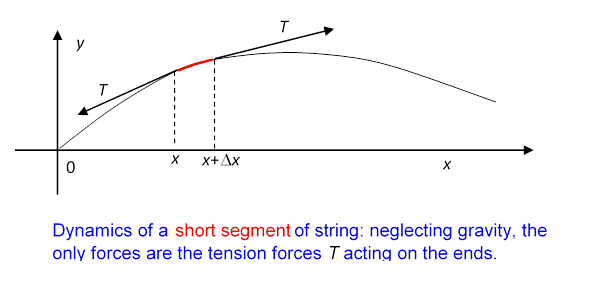

Everything there is to know about waves on a uniform string can be found by applying Newton’s Second Law, , to one tiny bit of the string. Well, at least this is true of the small amplitude waves we shall be studyingwe’ll be assuming the deviation of the string from its rest position is small compared with the wavelength of the waves being studied. This makes the math simpler, and is an excellent approximation for musical instruments, etc. Having said that, we’ll draw diagrams, like the one below, with rather large amplitude waves, to show more clearly what’s going on.

Click here to animate!

Let’s write down for the small length of string between and in the diagram above.

Taking the string to have mass density kg/m, we have

The forces on the bit of string (neglecting the tiny force of gravity, air resistance, etc.) are the tensions at the two ends. To an excellent approximation, the tension will be uniform in magnitude along the string, but the string curves if it’s waving, so the two vectors at opposite ends of the bit of string do not quite cancel, this is the net force we’re looking for.

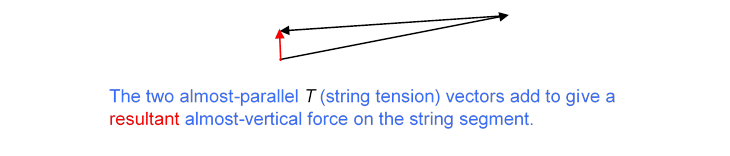

Bearing in mind that we’re only interested here in small amplitude waves, we can see from the diagram (squashing it mentally in the -direction) that both vectors will be close to horizontal, and, since they’re pointing in opposite directions, their sumthe net force will be very close to vertical:

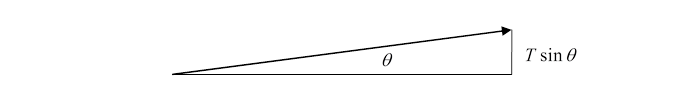

The vertical component of the tension at the end of the bit of string is , where is the angle of slope of the string at that end. This slope is of course just , or, more precisely, .

However, if the wave amplitude is small, as we’re assuming, then is small, and we can take , and therefore take the vertical component of the tension force on the string to be . So the total vertical force from the tensions at the two ends becomes

the equality becoming exact in the limit .

At this point, it is necessary to make clear that is a function of as well as of : . In this case, the standard convention for denoting differentiation with respect to one variable while the other is held constant (which is the case herewe’re looking at the sum of forces at one instant of time) is to replace .

So we should write:

The final piece of the puzzle is the acceleration of the bit of string: in our small amplitude approximation, it’s only moving up and down, that is, in the -directionso the acceleration is just , and canceling between the mass and , gives:

This is called the wave equation.

It’s worth looking at this equation to see why it is equivalent to . Picture the graph showing the position of the string at the instant . At the point , the differential is the slope of the string. The second differential, , is the rate of change of the slopein other words, how much the string is curved at . And, it’s this curvature that ensures the ’s at the two ends of a bit of string are pointing along slightly different directions, and therefore don’t cancel. This force, then, gives the mass×acceleration on the right.

Solving the Wave Equation

Now that we’ve derived a wave equation from analyzing the motion of a tiny piece of string, we must check to see that it is consistent with our previous assertions about waves, which were based on experiment and observation. For example, we stated that a wave traveling down a rope kept its shape, so we could write . Does a general function necessarily satisfy the wave equation? This is a function of a single variable, let’s call it . On putting it into the wave equation, we must use the chain rule for differentiation:

and the equation becomes

so the function will always satisfy the wave equation provided

All traveling waves move at the same speedand the speed is determined by the tension and the mass per unit length. We could have figured out the equation for dimensionally, but there would have been an overall arbitrary constant. We need the wave equation to prove that constant is 1.

Incorporating the above result, the equation is often written:

Of course, waves can travel both ways on a string: an arbitrary function is an equally good solution.

The Principle of Superposition

The wave equation has a very important property: if we have two solutions to the equation, then the sum of the two is also a solution to the equation. It’s easy to check this:

Any differential equation for which this property holds is called a linear differential equation: note that is also a solution to the equation if are constants. So you can add togethersuperposemultiples of any two solutions of the wave equation to find a new function satisfying the equation.

Harmonic Traveling Waves

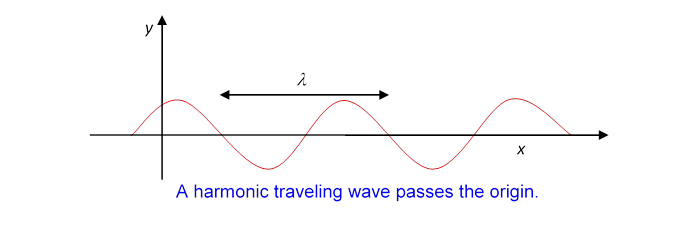

Imagine that one end of a long taut string is attached to a simple harmonic oscillator, such as a tuning forkthis will send a harmonic wave down the string,

.

The standard notation is

where of course

.

More notation: the wavelength of this traveling wave is , and from the form , at say ,

.

At a fixed , the string goes up and down with frequency given by , so the frequency in cycles per second (Hz) is

Now imagine you’re standing at the origin watching the wave go by. You see the string at the origin do a complete up-and-down cycle times per second. Each time it does this, a whole wavelength of the wave travels by. Suppose that at the wave, coming in from the left, has just reached you.

Then at second, the front of the wave will have traveled wavelengths past youso the speed at which the wave is traveling

Energy and Power in a Traveling Harmonic Wave

If we jiggle one end of a string and send a wave down its length, we are obviously supplying energy to the stringfor one thing, as the wave moves down, bits of the string begin moving, so there is kinetic energy. And, there’s also potential energyremember the wave won’t go down at all unless there is tension in the string, and when the string is waving it’s obviously longer than when it’s motionless along the -axis. This stretching of the string takes work against the tension equal to force times distance, in this case equal to the force multiplied by the distance the string has been stretched. (We assume that this increase in length is not sufficient to cause significant increase in . This is usually ok.)

For the important case of a harmonic wave traveling along a string, we can work out the energy per unit length exactly. We take

If the string has mass per unit length, a small piece of string of length will have mass , and moves (vertically) at speed , so has kinetic energy , from which the kinetic energy of a length of string is

For the harmonic wave

and since the average value , for a continuous harmonic wave the average K.E. per unit length

To find the average potential energy in a meter of string as the wave moves through, we need to know how much the string is stretched by the wave, and multiply that length increase by the tension .

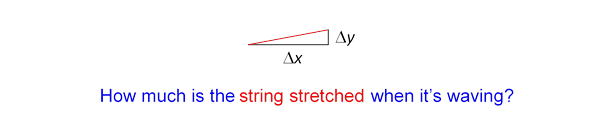

Let’s start with a small length of string, and suppose that the change in from one end to the other is :

The string (red) is the hypotenuse of this right-angled triangle, so the amount of stretching of this length is how much longer the hypotenuse is than the base .

So

Remembering that we’re only considering small amplitude waves, is going to be small, so we can expand the square root using the result

to find

To find the total stretching of a unit length of string, we add all these small stretches, taking the limit of small to find

Now, just as for the kinetic energy discussed above, since , the average potential energy per meter of string is

That is to say, the average potential energy is the same as the average kinetic energy. This is a very general result: it is true for all harmonic oscillators (excepting the case of heavy damping).

Finally, the power in a wave traveling down a string is the rate at which it delivers energy at its destination. Adding together the kinetic and potential energy contributions above,

Now, if the wave is traveling at meters per second, and being totally absorbed at its destination (the end of the string) the energy delivered to that end in one second is all the energy in the last meters of the string. By definition, this is the power: the energy delivered in joules per second, That is,

Standing Waves from Traveling Waves

An amusing application of the principle of superposition is adding together harmonic traveling waves moving in opposite directions to get a standing wave:

.

You can easily check that is a solution to the wave equation (provided , of course) and it is always zero at points satisfying , so for a string of length , fixed at the two ends, the appropriate are given by .

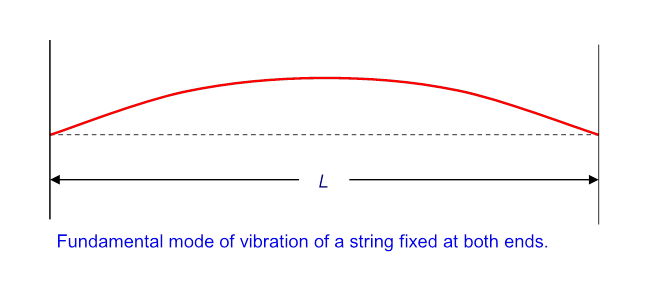

The longest wavelength standing wave for a string of length fixed at both ends has wavelength , and is termed the fundamental.

The -dependence of this wave, , is clearly , so

The radial frequency of the wave is given by , so and the frequency in cycles per second, or Hz, is

(This is the same as the frequency of a traveling wave having the same wavelength.)

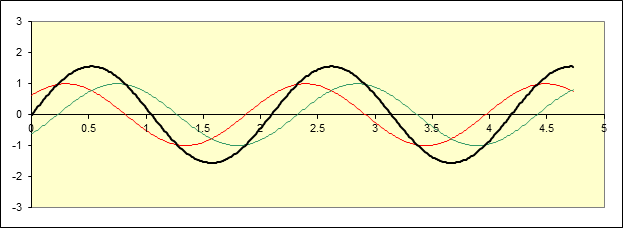

Here’s a realization of the superposition of two traveling waves to form a standing wave using a spreadsheet:

Here the red wave is and moves to the right, the green moves to the left, the black is the sum of the two and its oscillations stay in place.

But this represents just one instant! To see the full development in timewhich you need to do to get real insight into what’s going ondownload the spreadsheet from here, then click and hold at the end of the slider bar to animate.

Exercise: How do you think the black wave will move if the red and green have different amplitudes? Predict it: then try it on the spreadsheet. You might be surprised! (Try different ratios of the wave amplitudes: say, 1.1, 1.5, 2, 5.)